Hi, Everyone,

From the early days of COVID-19, we’ve been told to maintain six feet of distance between ourselves and another person in order to reduce transmission.

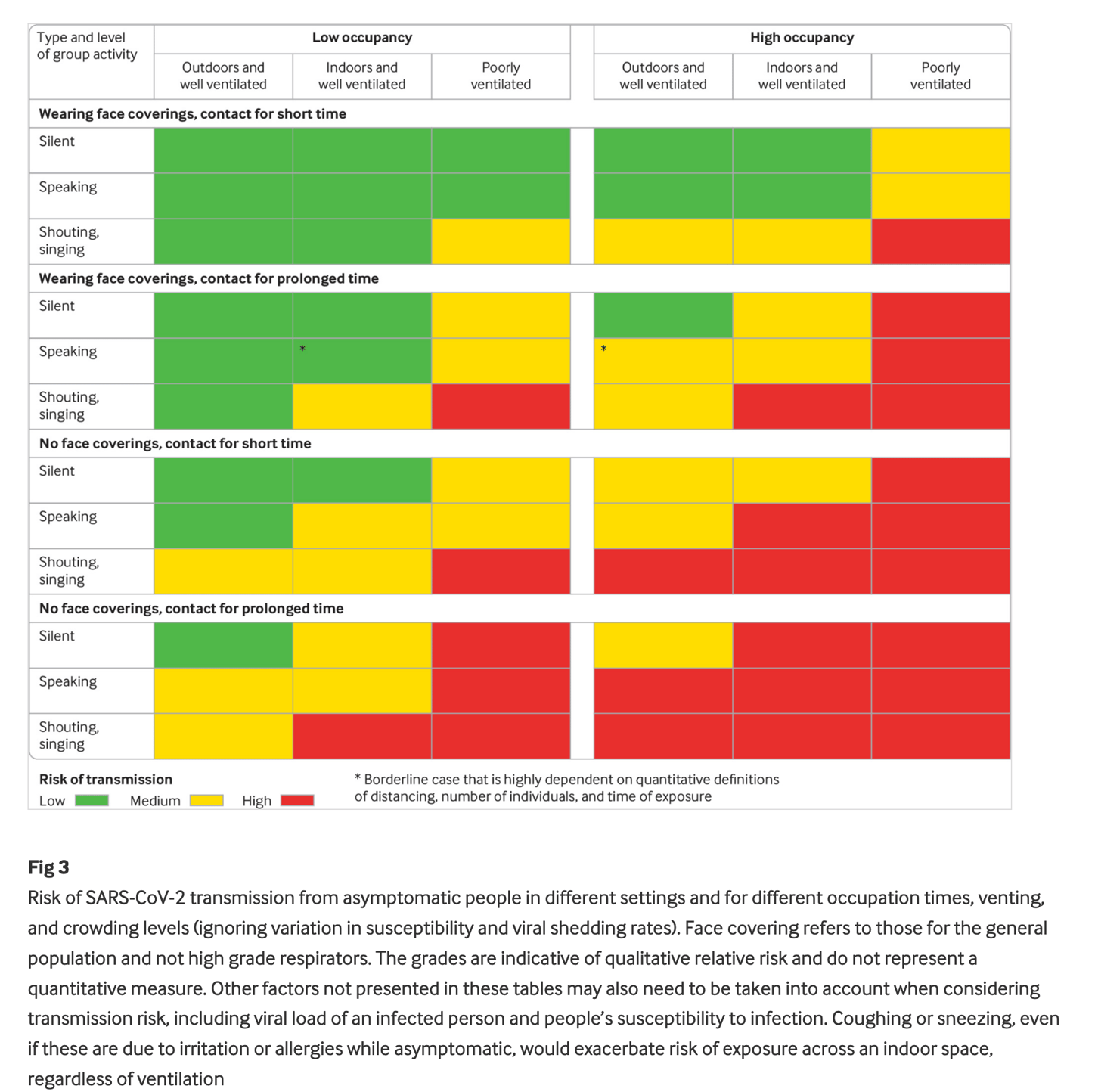

But this recommendation, while helpful in a general sense, doesn’t consider other important factors that affect transmission, such as the viral load of the emitter, duration of exposure, susceptibility to infection, and, perhaps most important, whether the environment is indoors or outdoors and whether face coverings are worn.

A new study published in BMJ took all of these factors into account with the intention of providing more nuanced guidelines for physical distancing. According to the authors:

“Instead of single, fixed physical distance rules, we propose graded recommendations that better reflect the multiple factors that combine to determine risk. This would provide greater protection in the highest risk settings but also greater freedom in lower risk settings, potentially enabling a return towards normality in some aspects of social and economic life.”

The paper is open-access, and I encourage you to read it. But I’ve excerpted the most important figure below. It illustrates how distancing requirements should change based on four key factors: ventilation, emission of particles (whether someone is silent, talking, or shouting/singing), exposure time, and face coverings.

Note that this grid applies only to asymptomatic individuals. The authors assume that people with symptoms should be self-isolating, and will tend to have a high viral load and “more frequent violent respiratory exhalations.”

(Figure from “Two metres or one: what is the evidence for physical distancing in covid-19?” BMJ 2020;370:m3223)

(Figure from “Two metres or one: what is the evidence for physical distancing in covid-19?” BMJ 2020;370:m3223)

This closely mirrors the formula I’ve been talking about these past several months for calculating risk: volume of exposure + length of exposure = risk of COVID-19 transmission. Ventilation, talking/shouting/singing, and face coverings are the primary determinants of the volume of exposure, and time spent exposed is the other factor.

What can we make of this? Again, according to the authors:

“In the highest risk situations (indoor environments with poor ventilation, high levels of occupancy, prolonged contact time, and no face coverings, such as a crowded bar or night club) physical distancing beyond 2 m and minimising occupancy time should be considered. Less stringent distancing is likely to be adequate in low risk scenarios.”

In other words, six feet of distance may not be adequate when other risk factors are more pronounced, while less than six feet may be enough when other risk factors are low.

For example, if I’m hiking outdoors, I’m not concerned about passing another hiker on the trail, even if neither of us is wearing a mask and we come within three feet of one another. Using the grid above to evaluate this risk, we’re both silent, we’re outdoors in a well-ventilated area, and the time of exposure is very brief. That puts us in the “green” area of low risk.

Of course, this does assume that we are both asymptomatic (if infected at all). If one of us were symptomatic, but not self-isolating, the risk would be slightly higher—but likely still very low.

As the authors suggested in the introduction, understanding these nuances and updating recommendations accordingly is an important step toward resuming a more normal life.

If we better understand which environments present the highest risk, we can focus our attention on avoiding or mitigating that risk—while giving ourselves more freedom in lower-risk settings.

In health,

Chris